Ripley,” “Boogie Nights”), are among the most memorable of recent decades. His screen portraits, whether in starring roles (like his Oscar-winning turn in “Capote”) or supporting ones (“The Talented Mr. Hoffman is one of the finest actors of his generation is beyond dispute.

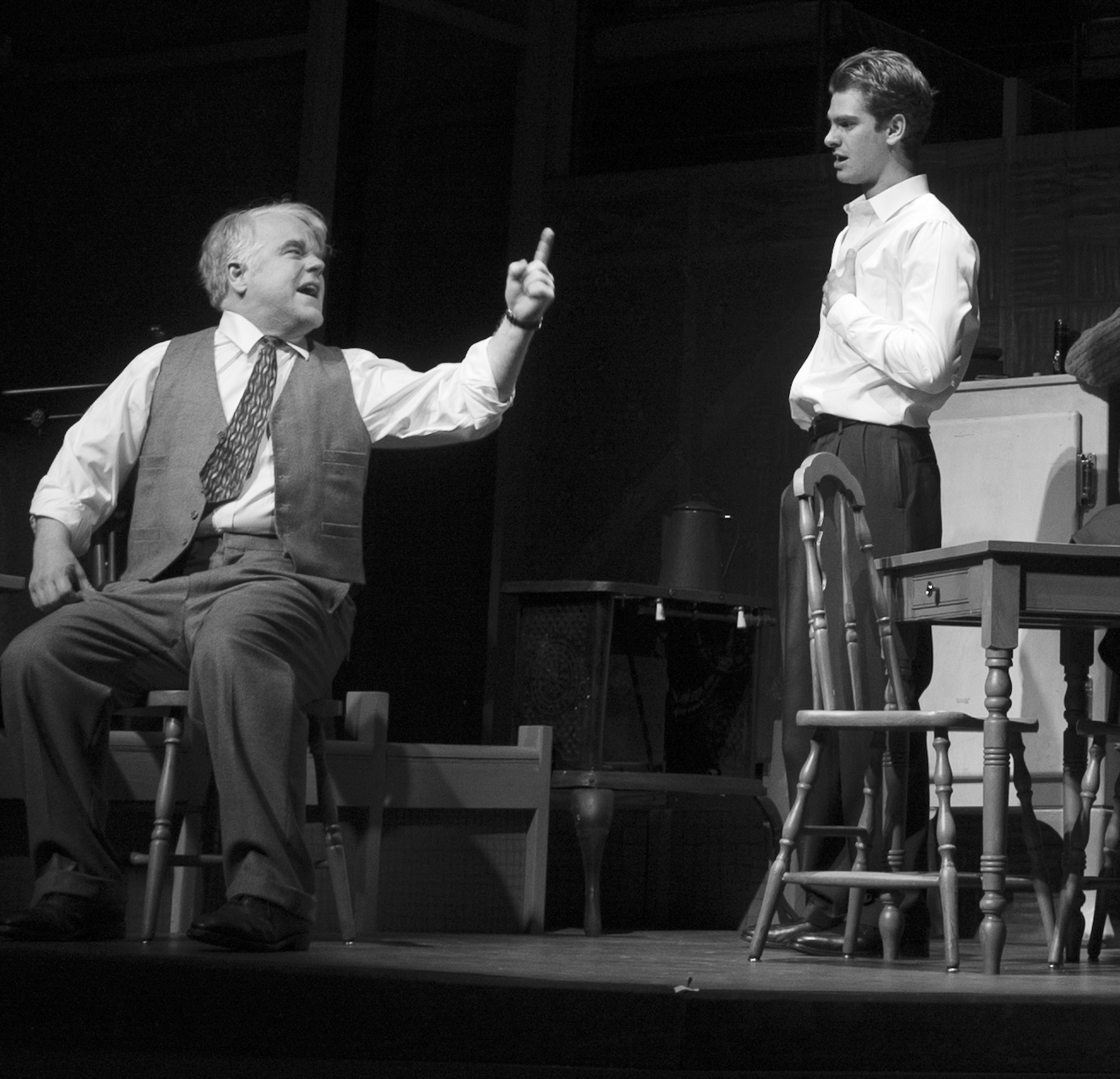

I don’t know what it is, but I can’t cry.” And at the production’s end I found myself identifying, in a way I never had before, with the woman kneeling by a grave who says, “Forgive me, dear. Yet the tears that brimmed in my eyes in those initial wordless moments receded almost as soon as the first dialogue was spoken. Nichols for vouchsafing us that glimpse of a watershed opening night in American drama, an uncommon gift from one theater lover to many others. It’s a beautiful, lyrical, ghostly vision - appropriate to a play in which an idealized past haunts an unforgiving present. So what you’re seeing and hearing at this production’s beginning is much what audiences at the Morosco Theater must have experienced in 1949. In an inspired choice he decided that for this revival, which stars a deeply thoughtful and uncomfortably cast Philip Seymour Hoffman, he would recreate the original visual and aural landscape devised by the set designer Jo Mielziner and the composer Alex North. Nichols - the enduringly fertile, award-laden director of stage and screen - had seen “Death of a Salesman” as a teenager some 60 years ago. How could it be otherwise? Because suddenly it’s all there before you: that set, that music and, above all, that immortal silhouette - the shadowed figure of a stooped man with sample cases, heavy enough to contain a lifetime’s disappointments.Īny passionate student of American theater is sure to get the shivers in the opening moments of Mike Nichols’s revival of Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman,” which opened on Thursday night at the Barrymore Theater. The curtain rises, and the floodgates open.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)